This post was originally published December 22, 2014 8:47 pm by padlock. It has been recreated in a rebuild of the site.

Marijuana Grassroots Advocacy Case Study

How a Small Group of Marijuana Activists With an Even Smaller Budget is Using Grassroots Advocacy to Win at the Local Level

As the holidays draw closer, you could have a fie pot party in Mount Pleasant, Michigan. You and your adult friends could each bring up to an ounce of marijuana and toke up as you have your eggnog, gingerbread and other holiday treats — all without any fear of the local police crashing through the door.

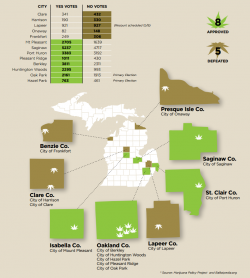

Thanks to voters who supported a legalization measure in November, the personal use of marijuana is now perfectly legal in Mount Pleasant. And Saginaw. And Berkley. And Port Huron, too. Indeed, this year was a big one for supporters of legalization in Michigan, who won referendums to liberalize marijuana in eight of 13 towns across the state — all on a budget so small, it would make most advocates in Washington gasp.

Of course, the slew of victories was no coincidence. Rather, they were the result of a highly orchestrated advocacy campaign designed to build momentum for legalizing the drug across the Wolverine State. Whether or not they achieve that goal, the effort could serve as a model for other advocacy groups who want to affect change and need to look outside Washington to do it.

“What it’s designed to do is to send a message to the Capitol that the population centers around the state really want to see a signifiant shift in the way personal possession laws are treated,” said Chris Lindsey, a legislative analyst for the Marijuana Policy Project, which advocates for marijuana legalization nationwide. “The strategy is to change local ordinances. At a certain point the legislators have to look at that and say, ‘why do we maintain criminal penalties when most of the voters in the state do not support that?’”

Planting the Seeds

The marijuana activists in Michigan are following a path well worn by advocacy groups that cannot get legislation in Washington. When issues cannot pass in Congress, advocates often look to the states. And if they cannot win in state legislatures, they sometimes turn to the locals. Over the years, advocates have used a state-focused approach to push everything from same-sex marriage initiatives to electricity deregulation. It often works. And it appears to be gaining traction in Michigan.

But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. In Michigan, the cities and towns were relatively small — turnout in some cases was in the hundreds — and the margins were sometimes narrow. In Lapeer, for example, voters were so split that the measure failed by a mere six votes, and a recount is underway.

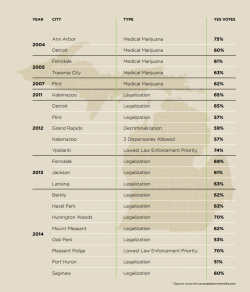

Winning the Weed War in Michigan*

With a small group of volunteers and an even smaller budget, marijuana advocates were able to win ballot measures in 8 out of 13 cities and towns across Michigan in the primary and general elections. Here’s how they fared.

Gerry Gunster, a veteran issue advocacy professional and CEO of Goddard Gunster in Washington, said ballot measure campaigns are won by leveraging solid research, tapping into local concerns and nuances and — perhaps most important — tying the marijuana issue to the self-interest of Michigan voters.

“If you want to convince voters that decriminalizing marijuana is in their best interests, you have to explain how the issue will impact them at a local, personal level,” he wrote in an email. “When we’re talking about local initiatives and referenda of any kind, connecting with the self-interests of voters often means making your issue feel tangible to the voter.”

Listen to the Polls

Because every state, city and town is different, local knowledge is as important to ballot initiatives as it is to hunting and fihing. Those who know the local terrain and waters will be the ones who come home with the prize.

“Knowing your territory inside and out is a fundamental fist step to filding a local campaign,” Gunster wrote. “That means hiring local experts is key. These ground teams and consultants will understand the nuances of your issue better than anyone.” Thereafter, polling becomes the campaign’s best friend, providing a radar that shows where the issue is gaining traction and which messages are resonating. This allows campaigns to allocate resources accordingly.

“Research should guide your every step,” Gunster wrote. “Research helps a campaign pinpoint effective messaging. But it takes discipline to adhere to those fidings—no matter what. Too often campaigns fail because someone decided to go off message.

“Remember: The research doesn’t lie. Avoid what we call ‘the false consensus effect,’ whereby you guess at what messages will resonate with your target audiences. When it comes to predicting the behaviors of others, your gut isn’t good enough. Listen to the polls.”

Gunster also is a big believer in fiding third-party advocates such a community leader, a business owner or a local mom, to carry the message. “Whoever they are, they should be respected by your community,” he wrote. “No one wants to hear messages about their community from an outsider. Your third-party messengers should always serve as the face of your campaign.”

Momentum for Marijuana

So, how did the marijuana campaigns succeed in Michigan? The strategy is not too different from the playbook that Gunster described. And, while the laws and regulations will be different in every state, advocates elsewhere can learn something useful from Michigan’s marijuana campaigns.

For starters, the Michigan activists had some national momentum on their side. Colorado and Washington passed legalization measures in 2012 and Oregon followed suit this year. Overall, 23 states and the District of Columbia now allow medical marijuana in some way and 17 have decriminalization measures of some sort. The federal government has made it clear it will not move to block such efforts, and activists expect to see attempts in states like Arizona, California, Nevada, Maine and Massachusetts next.

Some advocates say public sentiment has swung, and this is akin to the fall of prohibition in the 1930s. Indeed, a nationwide Gallup Poll taken a decade ago showed almost two-thirds of Americans were opposed to legalization. In October, the poll showed they are narrowly divided, with 51 percent saying marijuana should be legalized and 47 percent saying it should not (the margin of error was four percentage points).

At the same time, public opinion is not the entire story. “Some news outlets want to attribute the success of decriminalization campaigns to a growing public tolerance of marijuana,” Gunster wrote. “But tolerance alone doesn’t explain the wins. Campaigns that made the issue of decriminalization important to voters can be credited with the successes.”

Momentum in Michigan

Indeed, the advocates in Michigan have been working for years and they started small. Michigan law allows an initiative to be put on the ballot in individual cities by obtaining signatures from 5 percent of registered voters. The initiatives change city charters, and thus can be used to target local marijuana laws. While this is a tall order in a large city with hundreds of thousands of residents, it is far more achievable in smaller municipalities.

“We can’t control the legislature and we don’t have the money for a statewide initiative,” said Chuck Ream, a former kindergarten teacher who is now executive director of the Safer Michigan Coalition. “The only thing we can do is keep lobbying and keep running local initiatives, which at least we can control. … We put them up there and we win. We don’t beg.”

The groups that are pushing changes to marijuana laws have developed messaging that resonates in some demographics. Often, it revolves around personal freedoms. But another line of argument — and perhaps one more useful across the political spectrum — is that law enforcement agencies should be using their time and resources to crack down on more meaningful crime.

“There is much more serious crime that goes unsolved and law enforcement should not be directing its resources going after people who are in possession of a small amount of marijuana,” Lindsey said. “It always comes down to law enforcement resources.”

Momentum for Marijuana

The liberalization of marijuana laws has taken place nationwide, and is expected to continue in 2016. The epicenter was in the west, where states like Oregon, Colorado and Washington have fully embraced legalization.

Using polling to identify areas that may be receptive, activists target towns and begin campaigns for signatures using only volunteers. In a small town, just four or fie volunteers can create a presence. In this year’s efforts, there were no email, social media or print campaigns — and defiitely no air time. Rather, the activists — some of them local — chatted up leaders at City Hall and then got out and knocked on doors.

“We would go and just ask the person if they were registered to vote and then give them the pitch,” said Tim Beck, the former owner of an insurance agency who is now chairman of the Safer Michigan Coalition. “Others we would go to festivals in the summer. It was one-on-one contact. It was just old fashioned … one-on-one hard work.”

Cost-Effective Advocacy

Because marijuana is a captivating topic, the campaigns also typically got news coverage, and so advocates could rely on earned media to get the word out. In cities like Mount Pleasant, where fewer than 4,400 people voted out of a population of about 26,000, the strategy was very effective. They won with 62 percent of the vote.

It was also very cost effective. The Michigan advocates were not floded with money from national organizations. Nor did they need it. Rather, the entire 2014 marijuana effort in Michigan was run with about 70 campaign volunteers, Beck said. The budget for campaigning in 11 towns (they took on 11 towns in the general election and two in the primary) was roughly $12,000, and most was used to cover legal expenses and the fees associated with getting on the ballot. In many cases, the volunteers paid expenses from their own pockets. For example, the recount in Lapeer cost less than $100 to enact. The campaign’s local attorney just paid it.

The strategy takes patience. But it does appear to be working. Pro-marijuana advocates have helped to install legalization and decriminalization laws in 17 cities and towns across Michigan since 2011. In fact, until this year, they had not posted any losses in municipalities.

Of course, as in all long-term campaigns, there have been some missteps. Michigan’s advocates point to the four losses (the outcome in Lapeer is still uncertain, pending the recount) in small, rural communities as an example of where they diverted from their playbook in order to experiment. “We dropped the ball,” Beck said “[We] should have drove up north, went down to city hall, talked to people and got a general idea of what was going in those towns. Shame on us…we didn’t do that…we would have had a better flvor of the community.”

Gunster said that, compared to candidate campaigns, ballot measures in general can be far less predictable.

“You aren’t asking individuals to vote for or against a human being, you are asking them to vote for or against an idea,” he wrote. “And that can be a challenge. Ballot measure campaigns can often be more volatile than candidate campaigns. The campaign graveyard is littered with ballot measures that at one time boasted broad support only to lose steam weeks or even days prior to an election.”

In the case of Michigan, the losses may not have a major impact on momentum. Marijuana advocates have won far more than they lost. But leaders were disappointed to see the undefeated streak end.

“It was very upsetting to me personally,” Ream said. “We lost in these little tiny places.”

MICHIGAN LOCAL ELECTIONS AND MARIJUANA VOTING

Building the Case

As for the prospects of a statewide referendum, leaders approach it with a healthy skepticism. The effort would require north of 250,000 signatures to get on the ballot and advocates estimate that the campaign would cost at least $1 million. Advocates say that statewide support in Michigan, which is home to nearly 10 million people, needs to poll close to 60 percent to attract well-fianced backers. And those polling numbers, they say, are simply not there yet. Support for statewide legalization hovers around 50 percent, not too far from the national average. Indeed, a statewide initiative it has been tried three times in Michigan, to no avail.

“When you are changing statewide laws, you are going to have a battle,” Beck said. “The political class is not as deeply threatened by local ballot initiatives as they are with state [initiatives]. We have not been able to fid anyone willing to do this. We have no interest whatsoever to attempt a statewide initiative unless we run very well in the polls.” Lindsey, who works for the national Marijuana Policy Project, which could provide some of the needed support, was not overly optimistic. “There has been talk about it,” he said. “I don’t know how much support we are really going to see for it. Voter initiatives are extraordinarily time intensive and cost a great deal of money.”

Said Beck: “We understand … we have no resentment towards MPP and no attitude towards it. The big money people want to see poll numbers. That’s the problem.” Meanwhile, however, advocates continue building the case town-by-town. They believe in the work they do, and that each victory brings tangible benefis. “My thing has always been ideologically based,” Beck said. “The drug war has been a total disaster in this country … it has wasted lives, it has wasted time. Its just downright wrong and deeply flwed.”

As a result of the local strategy, however, more than 1.5 million people in Michigan now live where marijuana is decriminalized, Beck said. As he put it, “We are building momentum.”